We’re thrilled to share a new initiative that we have recently formalized,

Author: Tamar Kupiec

It was fall, just a couple months into the year for Hannah Levy, a first-time teacher and graduate student instructor in IslandWood’s School Overnight Program (SOP). One of her students had been interrupting all day and threatened to compromise the experience for the entire field group. By late afternoon he had just about “boiled over,” and Hannah wasn’t sure how she would face this crisis the following day. But then she ran into Ray Cramer, IslandWood senior faculty, in the instructor prep room.

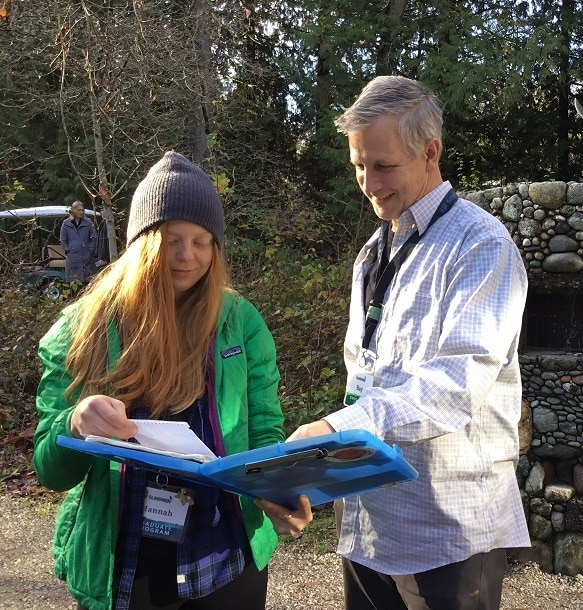

Hannah Levy and Senior Instructor Ray Cramer.

It was not a coincidence. As a mentor in the Graduate Program in Education for Environment and Community, he was making himself available to provide support when it was needed most—immediately. By design Ray’s office is not in the Administration Building but is instead in the Learning Studios, right off the instructor prep room and right up against the forest, where Hannah and the other grads spend most of the day teaching. Every week he not only “captures these moments of need,” but also schedules a minimum of three hours with each of his eight mentees.

That day Ray asked Hannah to analyze the situation, suggesting she dispense with universal qualifiers, which have a way of obscuring the truth. Did this student really “always” interrupt? Did he really “never” follow instructions? No, Hannah conceded. Together they identified patterns in his behavior and circumstances that made him more prone to interrupt. They then designed activities that created natural opportunities for sharing, so that this child could get the attention he craved through appropriate participation. “We had a better day the next day,” Hannah reported.

When Ray teaches his methodology course, he has a set of objectives that experience tells him are essential to the craft and which he introduces in an order that suits his students’ evolution. As a mentor, however, Ray is at the direction of his mentees. “The learning is best decided by those closest to the work, and that’s the mentee, not the mentor,” he says. The grads identify goals for personal growth or teaching strategies introduced in class that they want to work on. This is not to say that he abdicates his expertise. Rather, he practices patience. “It’s rare that a student brings up something I haven’t observed already,” he says. Still, he’ll wait for the situation, which not only illustrates his point most effectively but also connects to the student’s agenda. And he practices restraint. “You can always find things they might do differently, but they’re often tied to some personal narrative of your own.” Besides, he notes, too many helpful suggestions are not actually helpful. They just make it hard to focus.

Ray regularly observes Hannah in the field, possibly recording or transcribing, with commentary, everything that he sees and hears over a one-hour period. SOP, especially as a first-time teacher, can overwhelm with its newness—a new school each week, new investigations and community-building activities to master, new strategies to attempt. Hannah appreciates how Ray’s documentation allows her to see how she is integrating all these new materials into her practice. And she values the generous one-on-one time with her mentor.

Ray has seen Hannah make great progress in just these few months. For one thing, she hurries less yet achieves more. There was a time when fearing that her students would get bored, she’d run them all over campus, climbing the Canopy Tower, crossing the Suspension Bridge, looping back to the Dining Hall, and then out for a night walk. Today, she has the confidence to schedule fewer activities and allow the students to really “sink in.”

Hannah Levy and School Overnight Program students explore the beach.

Not only has she become a better teacher, she’s become a better mentee. She’s now more skilled at directing the process. Intuition about her own desires as an educator has given way to an ability to precisely name the skills she wants to develop, such as the “gradual release of responsibility.” Hannah initially found reviewing the video and transcription with Ray to be a “vulnerable practice.” It’s much less so today. Still, the vulnerability might not entirely disappear any time soon (Hannah acknowledges that it will take many years until she feels a sense of mastery in her newfound profession). But that’s OK. She trusts Ray—and she trusts herself.