As the COVID-19 crisis continues, it’s become increasingly clear that the entire field of environmental…

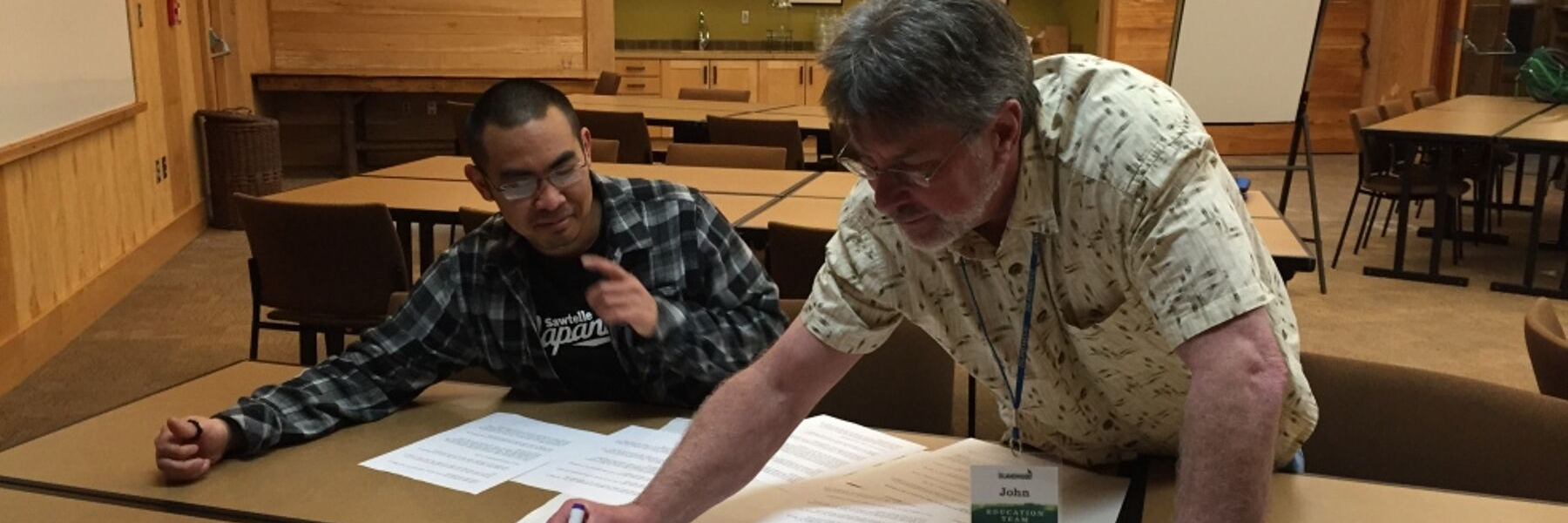

After completing his graduate certificate in Education for Environment and Community at IslandWood, Tom Stonehocker began a Master in Education and a Restoration Ecology Certificate at the University of Washington. He recently reconnected with John Haskin, IslandWood’s Senior VP of Education, for an interview.

How would you describe your philosophy of education?

I trained in elementary education; however, I’ve always chosen to teach beyond the classroom. My philosophy of education centers on providing direct experience with the subject of study—I am at heart an experiential learner. As an educator, I strive to make learning come to life for and with my students by accessing and creating environments that are rich with opportunity.

One example sticks in my mind from when I was a young educator. I was walking through the woods with a group of students, and we came across an old log on the ground. We examined the surface. It was mossy, still, and quite dead looking. The bark was soft. I pulled it away from the tree, revealing an abundance of life squirming beneath the surface. I can still recall the students’ faces as they leaned in to see. I bet we spent two hours exploring that log.

I’ve found that serendipity often provides some of the best learning opportunities. If you are open to the moment, and you know your students and have their learning interests in mind, you have the opportunity to make memorable, lasting, and meaningful learning experiences.

How has working with students in IslandWood’s graduate program helped shaped your view of education?

The most important work I do is support the development of new educators. The study of first-year teachers—their phases of development, the obstacles they typically face, and the most effective means of supporting them—was the topic of my dissertation.

Here at IslandWood, we want to create a place of trust, a place where students feel safe taking risks and being vulnerable, sharing their struggles and asking for and receiving help. We want to give them the tools to learn when things don’t go as planned, because that rub, that encounter with the unexpected, is an opportunity for growth.

Traditionally, we’ve thought that teachers learn their craft through books and lectures. But perhaps more influentially, they learn from the many years they spend as students in classrooms, when they develop their ideas of what it means to be a teacher and adopt the practices they see. Some researchers call this the “apprenticeship of observation.” The result of this “apprenticeship” can show itself in a difficult instructional moment, perhaps a student’s disruptive behavior or inability to grasp a concept. In these situations, novice teachers may default to strategies that they experienced as students, even if they’re not the best ones. Part of our work at IslandWood is challenging those previously held belief structures and supporting the development of new and diverse models of instructional behavior.

How do you work directly with the graduate students?

In the winter, I teach a course called “Environmental Theory and Practice.” However, I start designing this course in August, when the new cohort of graduate students arrives. I spend a lot of time with the students, because I enjoy it, of course, but also because I am gathering information. I observe them in class, how they interact, how they respond to different group designs, the questions they ask. We often think of courses as bodies of knowledge that we give to students and expect them to master. Instead, I believe that our task as leaders and instructors should be to create meaningful learning experiences. To do so, you have to be a student of your students and adapt your curriculum to suit their needs while not compromising your ultimate goals.

In my course, we look at the trajectory of the environmental education movement. We begin with its cultural and historical antecedents during the time of the civil rights movement and the environmental crises of the late 50s and 60s. Then we move toward the present. Environment-focused education is really citizenship education. It’s about inspiring people to act, think, and care differently about the world around them.

To accomplish this, we consider four dimensions of our work: what we teach, how we teach, and where we teach, be it the outdoors, nature, or the built environment. Place is not simply the setting for the lesson; it is what makes concepts come to life. The fourth dimension of instruction is the student(s). To bring learning to life, we need to tailor our learning experiences to the needs and backgrounds of our students. The ability to tailor instruction, instead of just teaching what or how we have previously been taught, is a skill that takes time, practice, and reflection, and is best advanced in the presence of a supportive community of other novice instructors.

What contributions to the field of education (environmental or otherwise) has IslandWood made or is IslandWood making?

We are one of many resident environmental learning centers across the country. We are one of far fewer, whose mission and identity are grounded not only in the development of programs for children, but in the development of teachers.

I am proud of our intentional blend of theory and practice. Our graduate students follow a regimen of coursework and biweekly teaching in our School Overnight Program. We believe that teaching is a craft knowledge and that mastering this craft requires this movement between study and practice, these repeated opportunities to test, reflect upon, and refine instructional skills.

I am also proud of the work we do in mentoring, which isn’t something that many centers have the resources to do. Each graduate student is paired with a mentor. The relationship is clearly defined down to the frequency of observations and meetings (often several times within a teaching week) and the resources available for documenting and assessing progress.

We’ve become quite successful at finding the learning edge for novice educators. This learning edge can be thought of as the point at which teachers feel they are at the limit of what their skills and confidence have prepared them to do. The key to growth is to go further rather than default to previously held instructional models. Our program structures, both the mentoring and the concurrent academic support, providing grad students with a supportive push into new instructional territories.

What keeps you excited about the work that you do?

We live in an increasingly diverse country. Environmental concerns cut across culture, class, and race. And yet, the environmental movement has historically been predominantly white, and environmental educators have predominantly been white women. What excites me now is our work as an organization to support a more diverse and inclusive environmental education movement.

So, what are we doing? In our IslandWood program we are preparing our grads to teach across boundaries, particularly with experience and strategies to support multicultural education. In our Urban School Programs and the School Overnight Program, we are building programs for community with community. Our grads are learning these strategies in their classes and their collaboration with schools.

In many ways, the students who stand to benefit the most from an IslandWood education experience are the grad students. They are with us the longest, and we have the greatest opportunity to help them engage in meaningful ways in the preparation of their career. That’s the real gift.

Tom Stonehocker, a 2018 alum of IslandWood’s Education for Environment and Community graduate program, is currently working on a Master in Education and a Restoration Ecology Certificate at the University of Washington.