In May, IslandWood hosted “Seattle Stormwater Systems and At-Home Science Learning,” a virtual workshop for…

Author: Tamar Kupiec

An excited fourth grader from Viewridge Elementary lowered a bucket by a rope 15 feet down into the Thornton Creek Water Quality Channel. She brought it up slowly, the bucket full and heavy with water. Her classmates helped her lift it over the railing and lower it to the ground without spilling, craning their necks to see the water up close. Would it be cloudy? Would it be topped with a shimmering rainbow of oil?

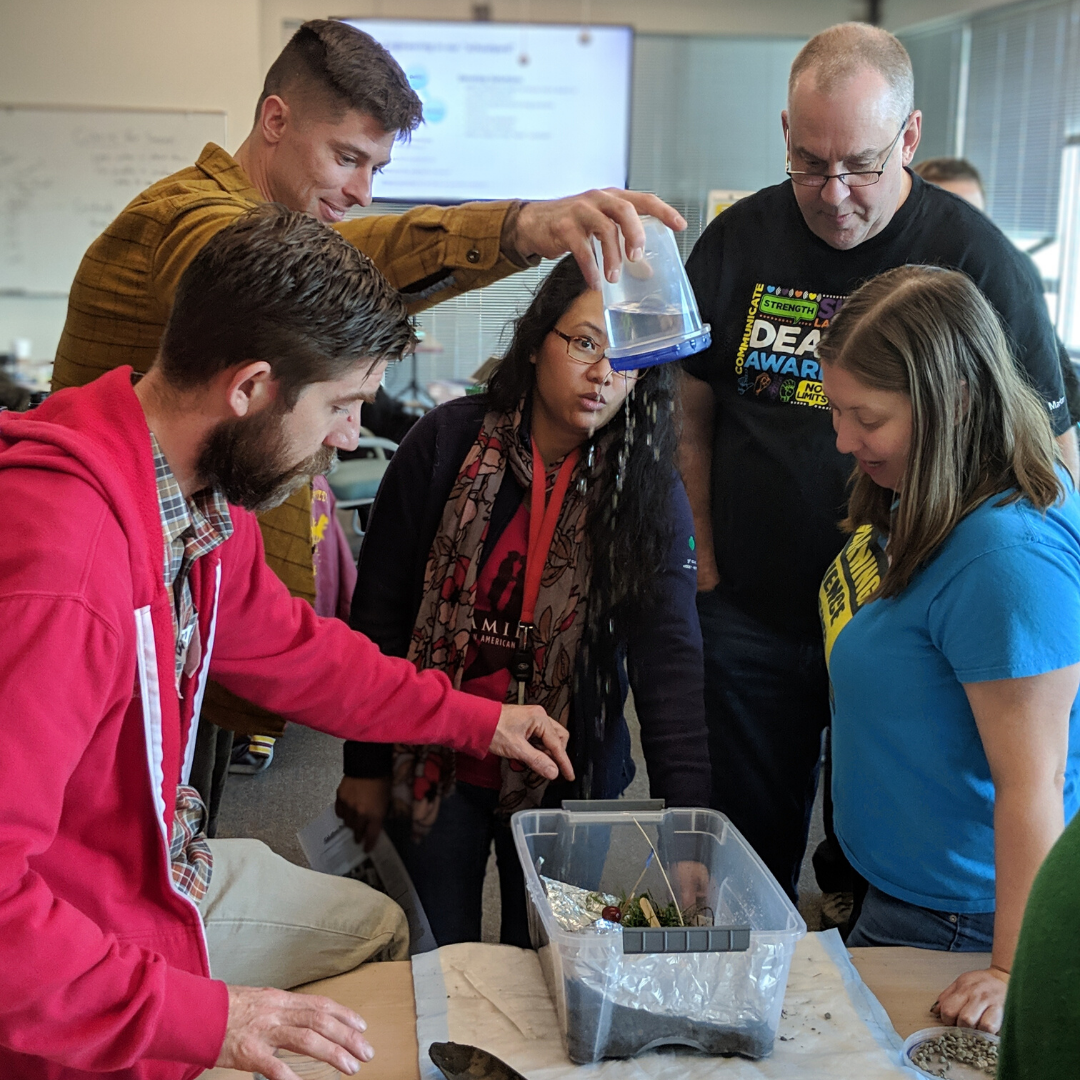

Students compare the turbidity of two water samples.

As participants in IslandWood’s Community Waters Field Study, the students would use their powers of observation, in combination with the tools of a scientist, to investigate this stormwater infrastructure site in the Northgate neighborhood of Seattle. How well does it do its job? their IslandWood instructor Emma Macdonald asked. How might it be experienced by the community’s stakeholders—neighbors, business owners, city officials, and even a resident heron?

Thornton Creek once ran through a pipe under an abandoned parking lot. Today, the creek cascades above ground winding through a vibrant housing community and lushly planted with native species. This exposed section of creek slows and cleans polluted runoff from 680 acres of urban land, preventing the flooding and erosion that once plagued the area, sparing Lake Washington, and revitalizing the neighborhood. It is a testament to what can be accomplished when community voice, municipal muscle, and engineering ingenuity join forces. It also makes an exciting real-world classroom in which to investigate stormwater, one of the most serious environmental threats to the health of Puget Sound.

In the space of four hours, these students would measure, calculate, and analyze; smell, touch, and listen; play, imagine, and empathize. It would be a morning of hard-earned discovery.

“The grass and the plants are slowing down the water!” called out one student at first sight of the channel interspersed with thick mats of grass. “Support that claim with evidence,” urged Emma. Much of the lesson would be devoted to gathering evidence to support this and other claims. They began at an upstream location, where the students tested the water quality of road runoff and the channel water collected with the bucket and rope. They strained to see the black and white marking of the secchi disk, used to measure turbidity, through murky water. They deliberated over the exact shades of green and orange on a litmus strip to accurately measure ph. And they visually inspected the samples to verify the presence of oil. They recorded their data and concluded the channel water was markedly cleaner than the untreated road runoff. Thornton Creek Water Quality Channel was doing its job.

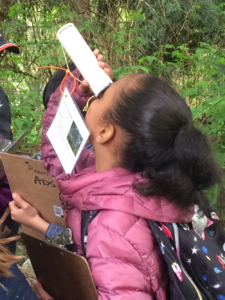

A student uses a densitometer to evaluate the tree canopy.

Leaving behind the upper channel, with its carefully controlled flow, reinforced banks, and curated plants, they headed to a more wild area downstream, where nature continued the work of slowing and cleaning stormwater. Following a trail through the thicket of plants and trees, Emma instructed the students to remain quiet and let their senses guide them. The students noted birdsong and the smell of skunk, or as it turned out, skunk cabbage. Here they would not only test the water but also conduct a plant investigation to determine if there was enough plant life to absorb the polluted stormwater. They drove a core sampler into the packed ground to analyze the density of roots. They used a rope quadrat to delineate an area in which to inspect the density of ground cover. And they peered through a plastic tube angled toward the sky, which acted as a densitometer, to evaluate the tree canopy.

The day had begun with a game, in which students were assigned a stakeholder identity and asked to determine how that stakeholder might be affected by a given stormwater scenario, such as a flood on nearby Fifth Avenue. The day would end with a return to stakeholder analysis. Students assumed their stakeholder identities once again to assess the success of the channel from multiple perspectives. The business owner would appreciate that a pleasant neighborhood would attract potential customers, suggested one student. Another remarked that at the downstream location a heron would not be frightened by the sounds of machinery and traffic. A neighbor would also appreciate the quiet, added Emma.

Research tells us that students learn best when subjects are connected to their own lives. The students in Kim Adsit’s class live with the inconvenience of stormwater, beginning in kindergarten when they learned to steer clear of the “huge lake” that formed in the middle of their playground after a hard rain. In class, her students have studied the science of stormwater and used models to design engineering solutions. However, Kim appreciates that the IslandWood field study pushes the conversation beyond “What could we do?” to “What did we do?” At the Northgate site, she says, “[Students] get to see what actually happened in the community and how [the channel] has positively impacted [it].” They also got to see the heron, who flapped his wings noisily as he took off from Thornton Creek, where he makes his home. Real life. No special effects required.