In May, IslandWood hosted “Seattle Stormwater Systems and At-Home Science Learning,” a virtual workshop for…

Author: Tamar Kupiec

How does something as precious as rain become an environmental hazard? When roads and roofs keep it from soaking into the ground, rain flows through gutters and storm drains into our waterways, picking up pollutants, such as lawn fertilizers, oil, and even sewage, along the way. This stormwater runoff has been identified by Washington State Department of Ecology as the most serious threat in urban areas to the health of Puget Sound. But there is so much that we can do in the design of our cities and the education of our students.

Students investigate a puddle in Seattle as part of the Community Waters Science Unit.

IslandWood’s Urban School Programs team and its partners have created school science curriculum, day programs, and teacher professional development to prepare students be part of the solution. This academic year, more than 7000 elementary school students will participate in our stormwater education in and around Seattle. They will investigate the causes and effects of runoff, design engineering solutions, and learn what they can do to improve the health of our waterways.

We’ve been doing this work for nearly two decades. During this time, we’ve found that science becomes more meaningful and students more engaged when what they are learning connects to their lives.

The immediacy and relevance of stormwater in the life of an elementary school student makes it a compelling entry into the world of environmental science and stewardship. Puget Sound is a great, big, and for some, relatively distant body of water. But stormwater, explains Derek Jones, IslandWood’s Brightwater Program Manager, is personal. It’s right there—visible, touchable—and it may be wreaking havoc in a school parking lot or contaminating a neighborhood creek.

For these reasons, our programs engage students in the study of stormwater problems close to home. Students are captivated by the scientific detective work entailed in gathering evidence and tracking down the cause. And the idea that flooding in the school playground might not be a matter of resignation, but a problem that can be corrected is empowering. From playground puddles to the wellbeing of the ocean, from a city neighborhood to city hall, the study of stormwater provides the foundation for understanding global issues and systematic solutions.

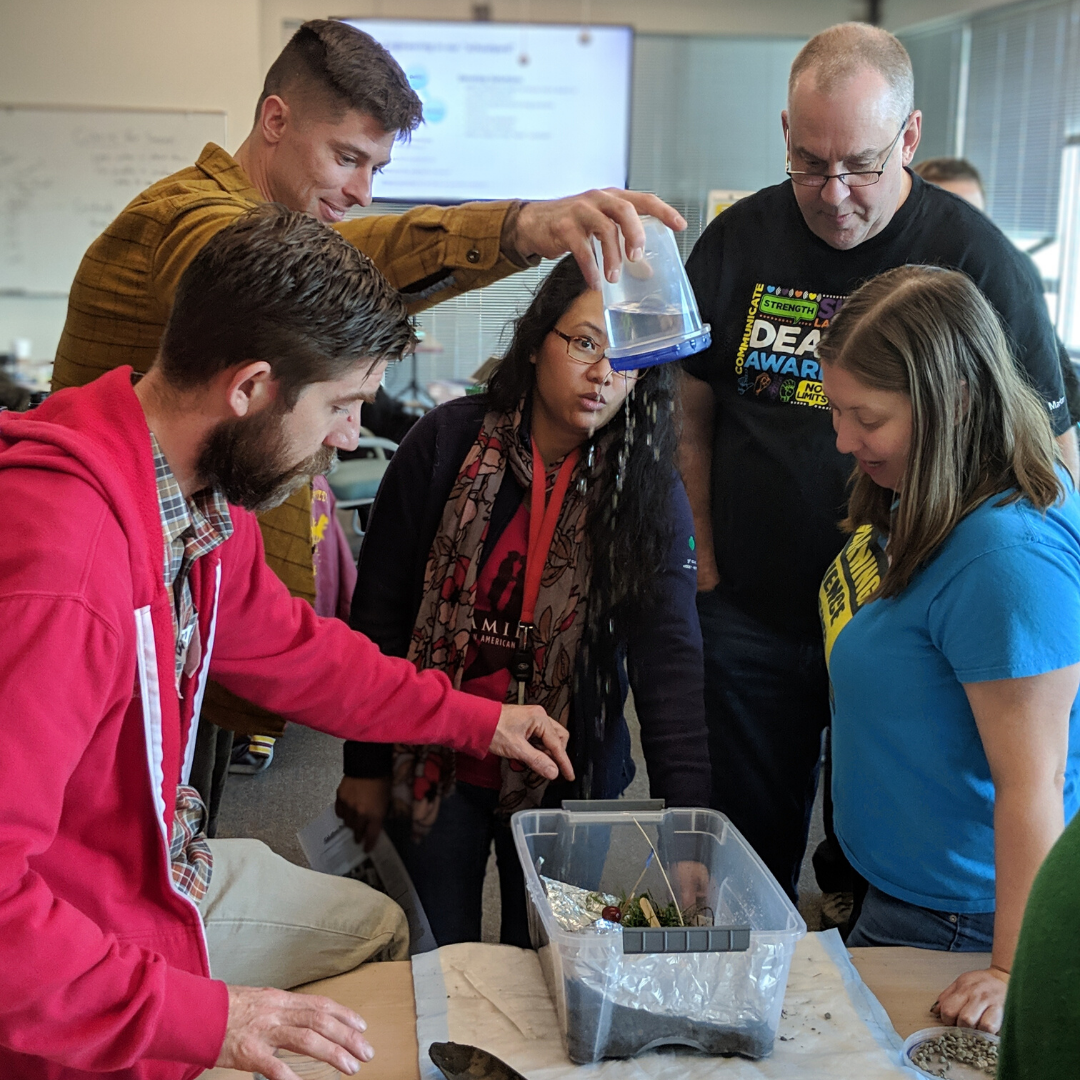

Our stormwater investigations introduce students to a range of scientific disciplines. Concepts in biology, chemistry, physics, and geology are needed to understand groundwater, erosion, water flow, and the action of pollutants. Students examine existing stormwater infrastructure and use the engineering design process to devise improvements: they define the problem, identifying constraints and criteria for success, and they use models to develop, test, and optimize solutions, such as cisterns, and rain gardens.

A student collects a sample from a pond at Brightwater.

Our approach also emphasizes the urban and social systems that contribute to stormwater problems and affect the feasibility of solutions. Students conduct stakeholder analysis and come to appreciate where the needs of the bike commuter, business owner, developer, and child may converge and diverge. They come to see that they too have a stake in what happens and a role to play in advocating for their needs.

Perhaps one day the students taking part in these IslandWood programs will be scientists, engineers, and urban planners. But already, teachers tell us they are seeing engaged students, informed neighbors, and children who care.