Bryant Elementary was one of the schools included in our pilot program of the School…

Author: Tamar Kupiec

Nadya Revchuk’s first impression of IslandWood is perhaps her most lasting. She came as a stranger, she says, and was welcomed as family.

Visiting Russian teachers stand on the suspension bridge.

Nadya is a botanist at the Vladivostok Botanical Garden and is training to be an environmental educator. She and Sergei Romantsov, a former volunteer at the garden and now a member of EarthCorps, had come to the Bainbridge campus as part of an environmental educational exchange, connecting botanical gardens of Eastern Russia with institutions in the Pacific Northwest. Their IslandWood host, naturalist and teacher Karen Salsbury, had visited Vladivostok as part of an earlier exchange. In her sixteen-year history with IslandWood, Karen has advocated for cross-cultural collaboration and friendship and has opened her home and the IslandWood community to teachers, students, and interns from around the world.

With the other Russian delegates, Sergei and Nadya would hike the trails at Lake Crescent, admiring the mountains that rise from the water, and stroll the groomed paths of the University of Washington Botanic Gardens. They would experience the trails of IslandWood, however, in a very different way—walking quietly and watching closely, not to catch the call of a marsh wren or discover a trillium in the shade of a cedar, but to observe a teacher and her students in the School Overnight Program (SOP).

This was not the first time that Nadya had made the almost 5000-mile journey from Vladivostok to IslandWood. She was here in 2010 as part of an earlier Russian exchange for a brief but tantalizing visit. When Nadya returned home, she put together a presentation for local schools on the use of case studies and stories by IslandWood instructors. Nadya and Sergei were here today for a more comprehensive visit and to gather other such techniques for engaging and educating students.

Nadya and Sergei met with IslandWood faculty to discuss pedagogy and program design. But it is one thing to read and hear about a philosophy of education and quite another to see it enacted with actual children. They were deeply affected by the experience. Certainly, they saw striking differences in the teaching methodologies practiced here and at home, but they also recognized a kinship between Russian culture and the environmental education taking place at IslandWood. “In the tradition of Russian families,” Sergei explained, “it’s very sacred to spend time outdoors, and now more families realize that that’s the way they really want to spend their free time—enjoying and learning in the outdoors with their kids.”

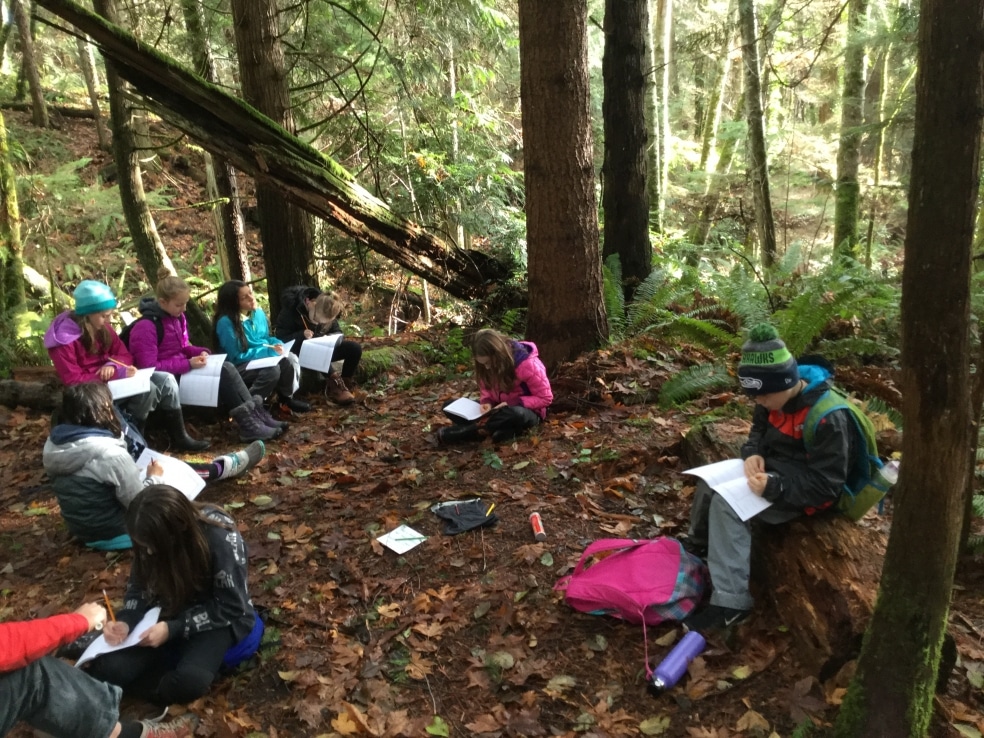

The kind of learning Nadya admired at SOP takes time. Lessons are based on “perception,” she commented, with teachers inviting children to use their senses to wonder and notice, a marked difference from the rote memorization typical of Russian education. She expects that this different way of learning will be well received in Russia, but concedes that the method is slower. Nadya also saw that rather than demand immediate obedience as is the way in Russian schools, SOP teachers treated their students as individuals and adjusted their teaching style and lesson plan accordingly. “The instructor waits very patiently for the kid to join in the process,” she recounted, “and sometimes it takes half an hour, maybe more… The instructor waits for the kid to show desire to be part of it, and the desire helps learning.”

Sergei, who describes his decision to leave the field of transportation to pursue a career in environmental education as “following [his] heart,” well knows the importance of passion in education. At IslandWood this desire to learn, Sergei added, is nourished by freedom. “What I like here,” he says, “is that kids are allowed to explore the wilderness and be curious as much as they want to be, and I think that’s something that we don’t have now [in Russia]… [this exploration] helps them to learn about the environment, to learn about themselves.” Children at IslandWood, he observed, are also encouraged to explore their relationships with one another, which trains them to be “sensitive and thinking human beings.”

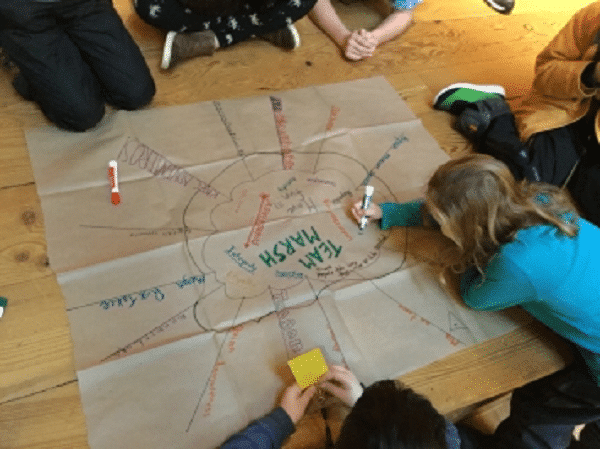

School Overnight Program students collaborate on an informational drawing about their time at IslandWood.

Freedom does not mean lack of structure. In fact, the learning environment at IslandWood is carefully regulated and protected, and teachers project authority. Rather than assailing students with prohibitions, Nadya observed, the teacher and her students agreed upon certain rules which were invoked only when necessary. Nadya was also struck by the supporting role played by chaperons. When Nadya and Sergei tried to pass a group of children who were taking part in a silent hike, in which the trail is marked with written prompts to encourage reflection and ignite the senses, the chaperon asked them to wait so that the children could walk at their own pace.

Patient and empathetic teaching. Freedom balanced by responsibility to the group. This is what most impressed Nadya and Sergei during their day with the School Overnight Program. They left with not only admiration and aspiration, but also the pedagogy with which to practice this approach at home.