If you look at the leaves of the salmonberry, a plant that thrives in the…

Author: Caroline Bargo, Graduate Student

The thought of handing over a six-inch knife to a child you’ve only just met makes many educators anxious. I too was wary when I first started my career in garden education. With practice, though, the responsibility and trust that come with using a knife have become two of my favorite things to give children.

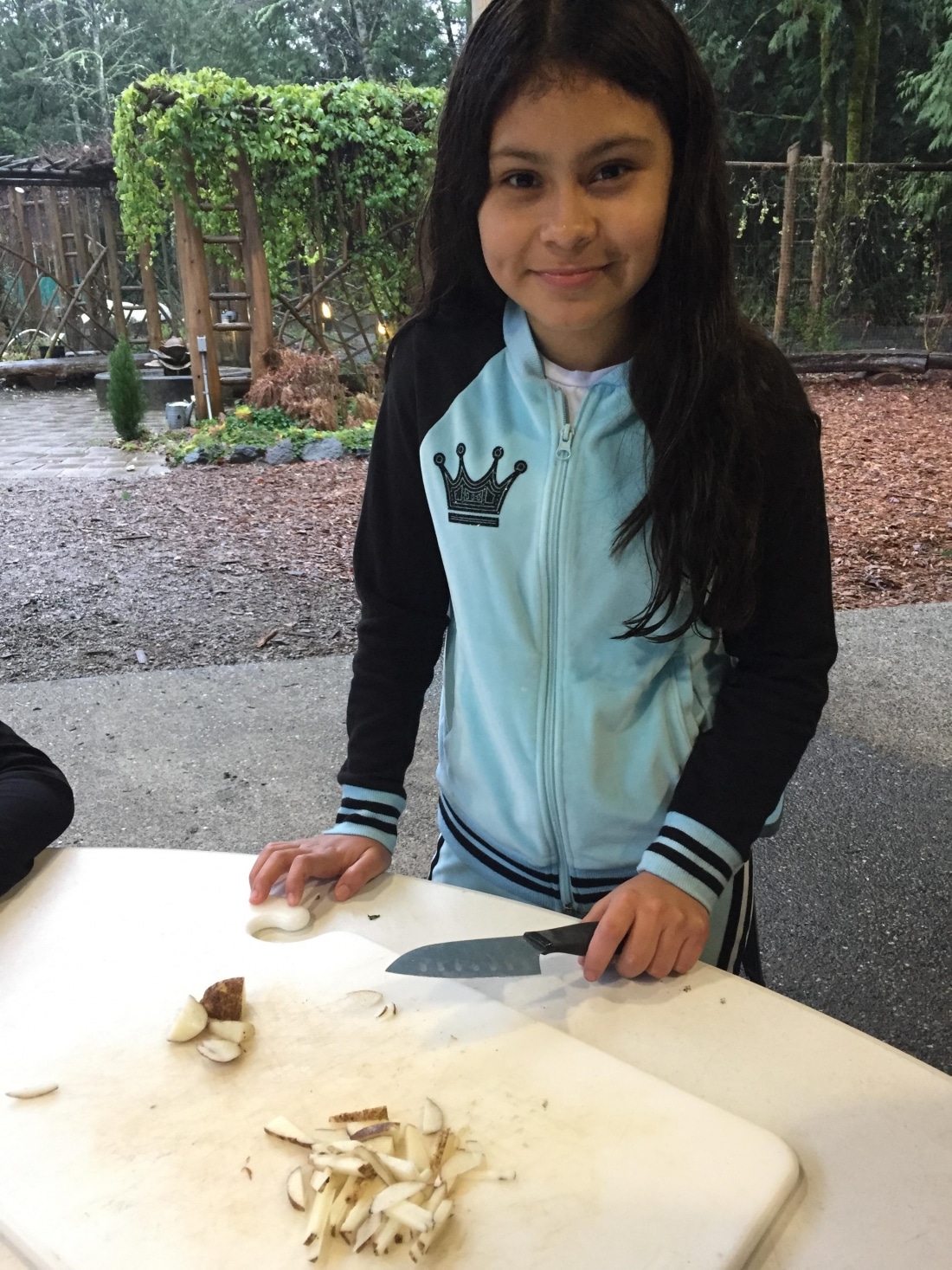

A student chops potatoes in the garden kitchen.

Before I came to IslandWood I managed an elementary school garden in Goleta, California. Some of my fondest memories are harvesting, chopping, and cooking in that garden. As you can imagine, my California garden was a bit different than those you find in Washington.

People here giggle when I tell them I could grow peppers and lettuce outside all year. I never had to winterize my garden and rarely thought of the seasons, because I knew that the sun would generally shine enough for almost any plant. With a view of the Santa Ynez Mountains behind the garden and the Pacific Ocean just over the bluffs, this patch was a spot where fog and sunlight met, creating a premium school garden location. Although the facilities in the garden were sparse (I had to connect a hot plate to a portable classroom sixty feet away with three extension cords), cooking with kids became a passion of mine.

Cooking, of course, requires knowledge of how to use a knife, which can be intimidating for some children. When I bring my field groups to the IslandWood garden and we take over the outdoor kitchen, my students generally shriek in delight (and sometimes a little anxiety!) when I pull out the roughly six-inch chopping knives we provide students. My students and I harvest whatever is available from the garden, be it herbs like sage and rosemary for what we call community bread or cucumbers and carrots for garden sushi. Students wash and dry their finds and we begin the process of chopping. I demonstrate what I like to call “the claw,” in which the non-dominant hand is placed over the top of the blade with the fingers wrapped around the item to be cut, while the dominant hand holds the knife handle. This allows students to steady the item to be chopped while keeping fingers safely out of reach. I teach them proper chopping technique by showing the rocking motion from the front to the back of the knife, with small steps forward and backwards to make sure everything gets chopped evenly. We practice the proper way to hand off the knife to the next person. When chopping round things like apples or pomegranates, I help them by cutting a flat edge so that the item will balance, but after that I hand over the reins and allow them to do the hard work.

The first week back at the School Overnight Program from winter break I had a student whom I just couldn’t seem to connect with. Despite my best efforts, he was angry about being at IslandWood. I knew that his anger stemmed from something larger and was determined to show him that I was going to be a consistent adult in his life, even if it was just for the next three days. After a few tears shed on my part after the first day, I decided that he could be angry, yell at me, and curse, but I would remain neutral. On Tuesday, I tried this method out with mixed results. With a lot of support from my fellow instructors, my chaperone, and the staff here at IslandWood, I went into Wednesday determined to remain consistent.

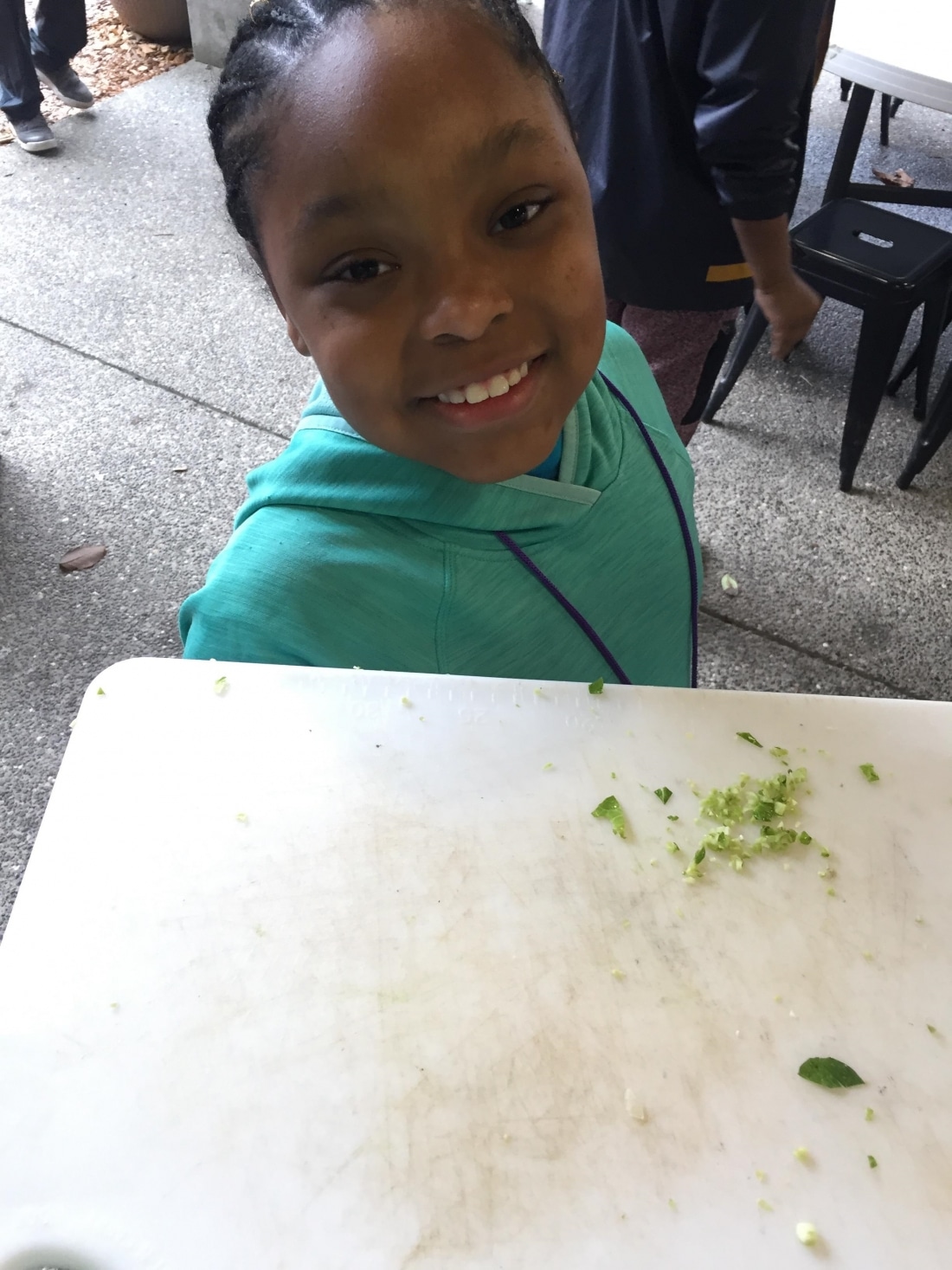

A student holds up a chopping board in the Garden Kitchen.

We visited the garden that day and honestly, I was a bit nervous about allowing this child to work with a knife, but he was eager to engage and this was a rarity for him. We went through all of my standard knife procedures and I handed over the knife not knowing what to expect. In minutes, this student was a different child. He was calm and collected and shared stories of cooking with his mom. He concentrated on his task, diligently working in his own little world. His chopping skills were better than mine, and he was clearly very comfortable. As we chopped potatoes I felt closer to him than I’d felt all week. We all enjoyed the crispy roasted potatoes straight out of the garden wood fire oven, and I could tell my student was proud of his contribution to the group.

In our graduate classes, we are learning how to be culturally responsive educators, and one of the most important things we can do in this practice is to make meaningful connections with our students. Handing a tool that carries responsibility, such as a knife, to students who may not always feel like they are trusted in school, creates instant connection. Cooking with my students has been one way that I have connected with them fastest and oftentimes that connection is sustained the entire week. Giving that child a knife didn’t magically turn his week around. That responsibility did, however, allow me a window into the mind of my student to discover what makes him feel important, and that itself was well worth the effort.