Washington State formally adopted the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) in 2013, but to many…

Author: Tamar Kupiec

The fourth graders at John Rogers Elementary School in North Seattle had found their problem site: the parking lot behind their school. Just one rainfall could turn it into a giant pool of water. As participants in Community Waters Science Unit, they understood that the problem was not limited to this stretch of asphalt, but involved a complex system of impervious pavement and city sewers, absorbent soil and a creek flowing past their school grounds.

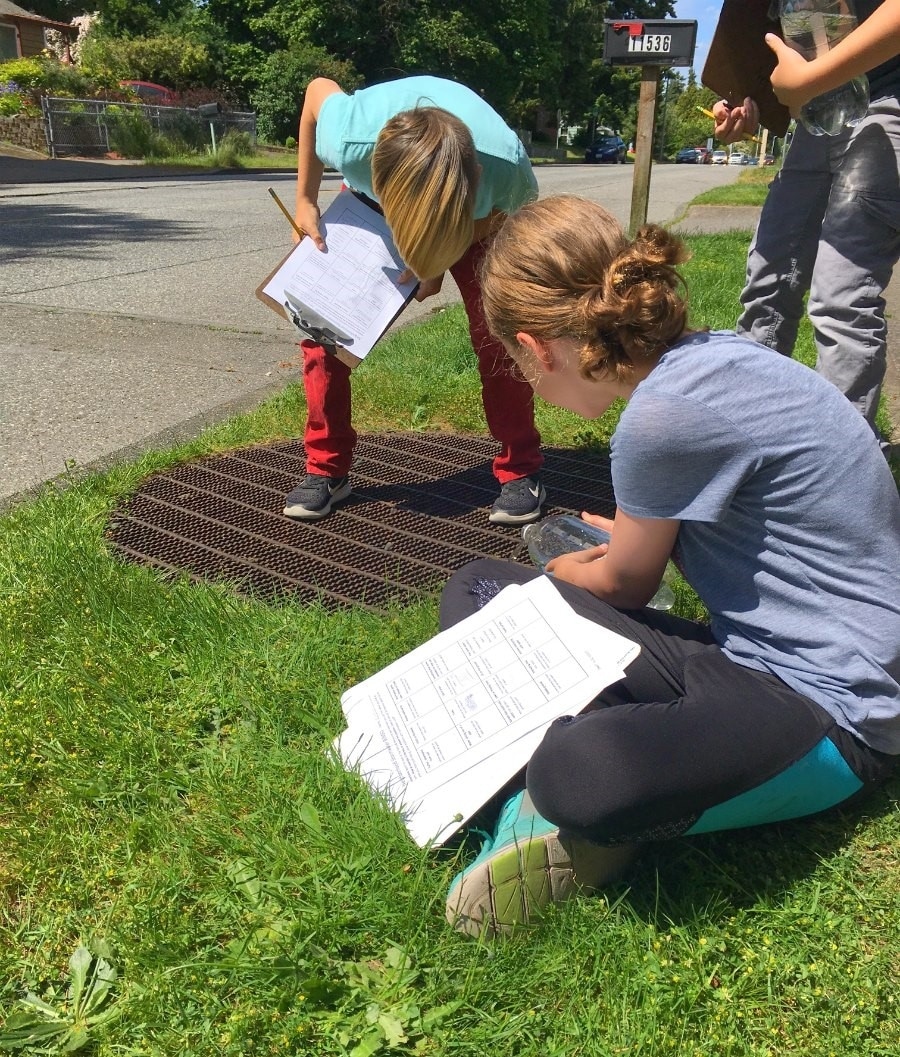

An educator leads students in an exploration of their local environment.

By the time they had zeroed in on the parking lot, the students were already experts in stormwater runoff. They had studied the way urban environments cause flooding; they had inspected city maps showing a subterranean world of pipes; they had compared the effect of water falling on tubs of dirt, with and without grass, to understand the role of plants in preventing erosion.

The students then inspected their schoolyard and surrounding area, observing and mapping the flow of water, considering topography, vegetation, and the location of storm drains. Their hands were dirty, their minds were full, and they were ready to figure out what was causing that pool of unwelcome water.

The Community Waters curriculum was developed by IslandWood and Seattle Public Schools to incorporate the new Next Generation Science Standards with emphasis on the engineering design process and community-based learning. Teachers are being asked to implement a new set of standards, tackle often less familiar engineering topics, and get their students out of the classroom and into the community. The curriculum, funded by King County, Seattle Public Utilities, and the Washington State Department of Ecology, provides teachers with not only content, but also direct support and professional development. In addition to the curriculum and background materials, they receive a customized guide to their school and community, which includes a school-specific map, pictures of built and natural features that influence stormwater runoff, and suggested routes for a walking field trip. IslandWood staff are available for a planning session and to guide teachers on a practice walk (or do the outdoor portion altogether so that teachers can watch and learn the first time through). Historically, IslandWood has focused its energies on working with students, but Community Waters marks a new direction for us. With this effort, we are collaborating with the district to support teachers as they deliver the lessons and make the curriculum their own.

Students investigate a storm drain.

Community Waters has been three years in the making. The curriculum was piloted three times, each phase eliciting an enthusiastic response and a round of revisions. This year it will roll out in approximately 30 schools, and next year is the district-wide launch. But Community Waters is still a work in progress. We’re enlisting teachers to participate in an online forum, fill out surveys, examine student work as part of a professional learning community, and possibly appear in an instructional video to help make the curriculum self-sustaining. In partnership with the district, we will continue to improve and refine the curriculum based on this teacher feedback and student work.

Now back to that parking lot. It was easy enough to find a problem this size. But in keeping with the engineering design process, the students had to define the criteria for success and identify their constraints, then research, develop, and test solutions. The class divided into groups, constructed models of their schoolyard with sand, gravel, tin foil, and the like, and finally applied and optimized their chosen solution. In the end, student groups came up with proposals, ranging from pervious pavement and rock trenches to a rain garden. They presented their findings to school administrators, but this is where the project ends—for now at least. The students are in fourth grade, the budget is tight, and they will have moved on to middle school by the time a city approval process could be completed. But for the fourth graders at John Rogers Elementary, a puddle now means so much more than some water to splash in or leap over.