Our Bainbridge Island campus may be quieter than usual, but it’s far from empty. Check…

Author: Tamar Kupiec

The walk to Port Blakely Cemetery, at the southwest boundary of the IslandWood campus, took over an hour. Team Ravine headed south on a well-worn route, but just past the Suspension Bridge, instead of continuing on to Mac’s Pond, they turned onto a spur trail. It wound through woods thick with moss and fallen limbs, the forest floor matted with leaves and tufted with sword ferns. Just before they emerged into the pleasant clearing of the cemetery, they stopped. Their instructor, Alex Guest, wanted to be sure they were ready. There would be one more lesson, one more admonition for respect, before she allowed them to enter. But why had they come? What could a cemetery possibly have to do with environmental education?

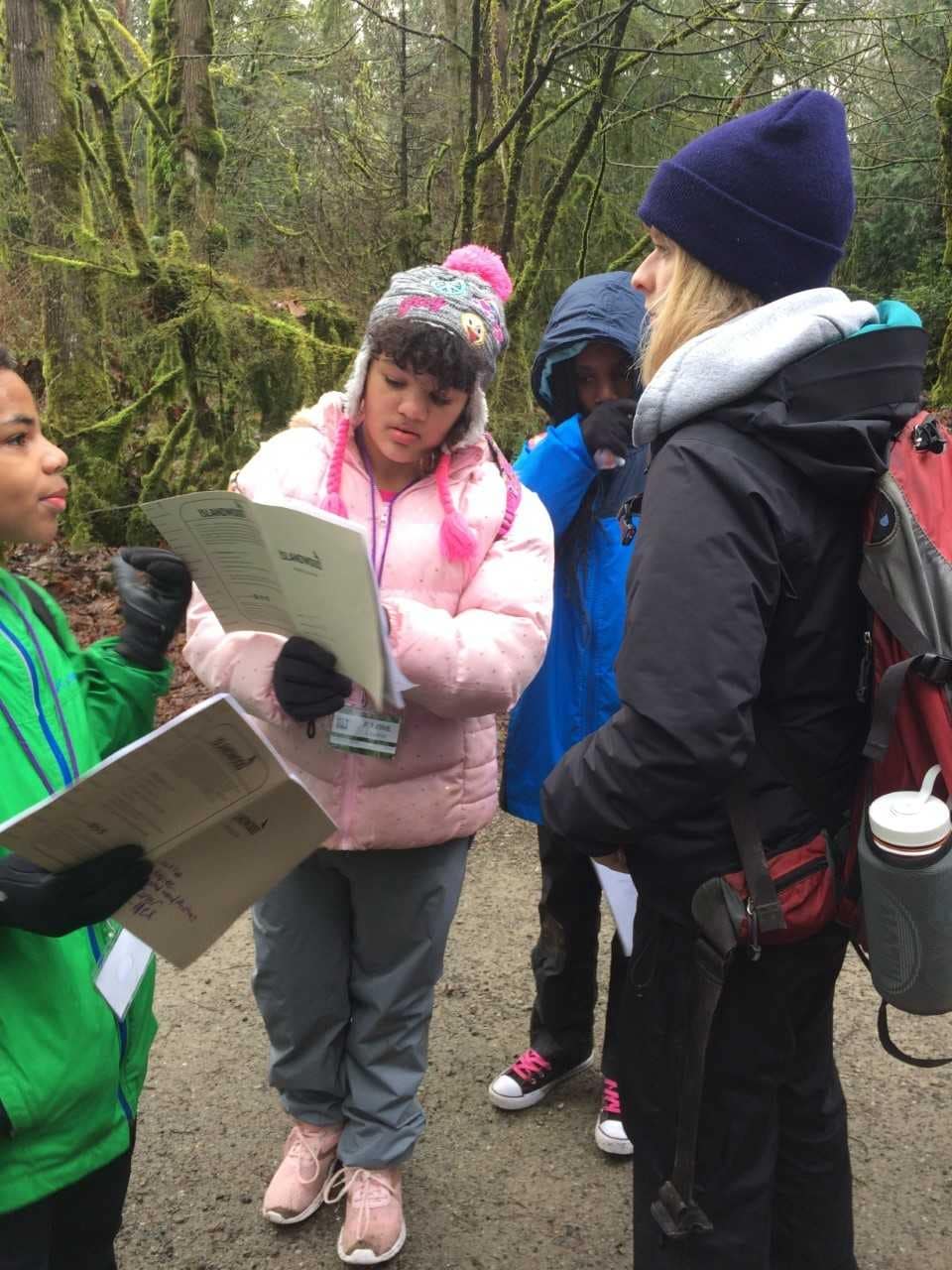

Students talking with instructor Alex Guest on their way to Port Blakely Cemetery.

Before setting off, Alex had asked her students a question: “Who has called Bainbridge Island home over time?” The answers were to be found here, in this private cemetery which expanded 20 years ago with the purchase of almost three acres from IslandWood. Ever since, the cemetery has allowed students in the School Overnight Program (SOP) to visit and learn from the history engraved in its stones. And so it is that generations of SOP students have learned about Tatsukichi Moritani (1917-2006), the son of Bainbridge Island’s first strawberry farmer. Moritani was placed in a concentration camp during World War II as part of the Japanese internment and ultimately returned home to continue the family farm.

For Alex, directing students to think about people and their relationship to the land is essential to her practice as an environmental educator. Like others in her field, she knows that forming an attachment to place supports environmental stewardship. IslandWood’s approach to environmental education includes natural history and ecology, as well as social studies. It fosters stewardship of environment—and community. Part of connecting to place is knowing what came before and taking part in what comes next. It means being a student of history and a participant in the present and future. This understanding and action are the makings of a steward, and habits of inquiry and caring participation are cultivated here at IslandWood.

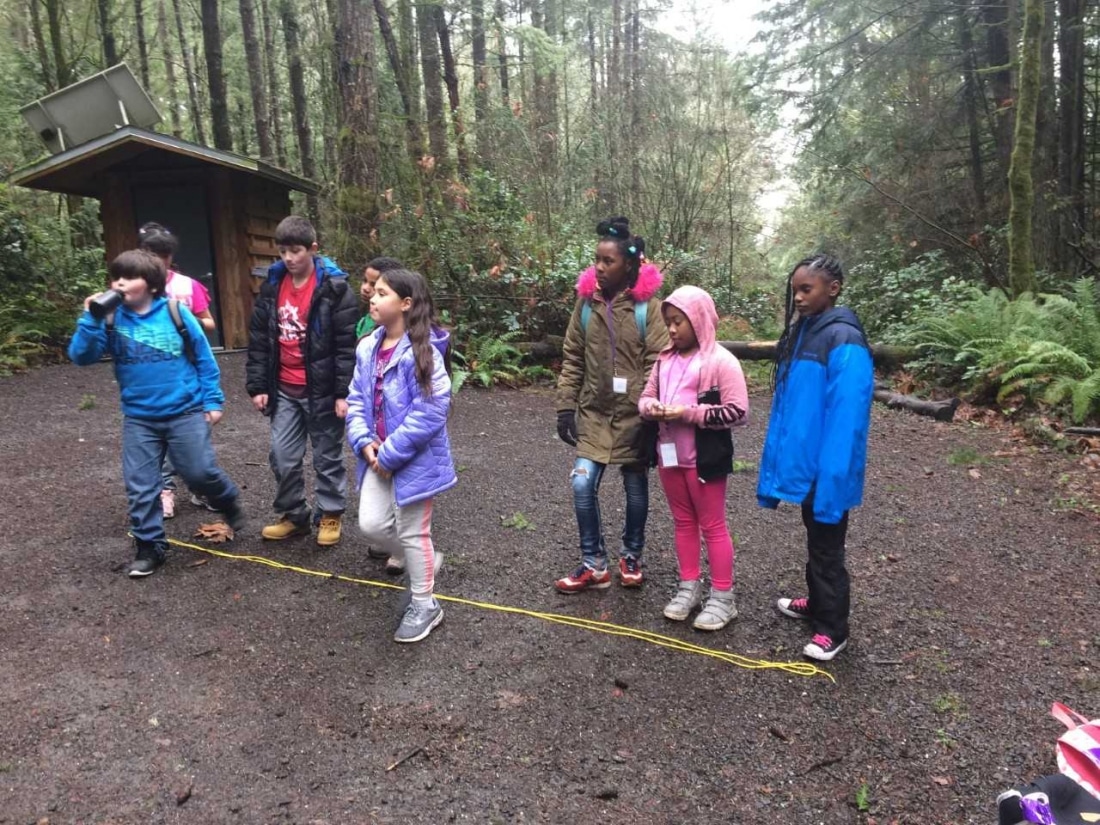

School Overnight Program students play the “Cross the Line” game.

In SOP vernacular, the sort of investigation that takes place at the cemetery is called “History Mysteries.” That final “s” is not a casual grammatical choice. It is meant to show that there are many stories to be told for every event and moment in history. Students often hike to Blakely Harbor, where they learn about the Port Blakely Mill—the massive scale of its operations, the clearcutting of the land that today comprises IslandWood. “By only telling that story,” Alex cautions, “it creates a space where that is the story, when it really it is a story.” She chooses to also tell the story of immigration. “So often white stories are the story. In the cemetery in particular, it’s obvious that people came from all over the world to this saw mill, which is an important part of [its history].”

Today, all that remains down at the harbor is the 100-year-old concrete building that housed the mill’s power generator. The mill town, with its ethnic enclaves, is gone, leaving the cemetery as the only experiential learning opportunity for SOP, a particularly intimate one. Curious students might scrutinize the other names and dates on Moritani’s gravestone. They might wonder at the existence of someone named Masaru. They might do the math (1918–1924) and deduce a tragically short life. Moritani was a real person, who brought his strawberries to market in a wheelbarrow and lost a beloved brother.

Alex grew up outside Boston, where cemeteries, often dating back to colonial times, are a fixture of most town centers. She feels at ease in these spaces, but she does not take the decision to bring a group to Port Blakely Cemetery lightly.

And so she used that hour-long walk as an opportunity to focus her students’ energies and practice the skills and behaviors they would need to appreciate and learn from the cemetery. Before setting out for the day, the members of Team Ravine had studied their maps and traced their chosen routes to the Suspension Bridge in magic marker. Deliberating at each fork in the road, they made slow progress, with the exception of the student designated captain navigator, who in her enthusiasm kept charging too far out in front. Alex gathered the group to discuss leadership etiquette, a precursor to what would be expected of them in the cemetery. They had not gone far, when they encountered a fallen tree across their path. “What do you think happened here,” Alex asked, using the minor predicament to practice the claim and evidence reasoning they would later use to infer from the languages and names on the gravestones the role of immigration in Bainbridge history.

At the final stopping place, Alex laid a rope on the ground. They would play a game called Cross the Line. “I invite you to think about your community. How is moving a part of your story?” she began. “Cross the line if you speak a language other than English at home.” Two children crossed. “Cross the line if you have ever lived some place other than Washington.” The children moved back and forth with each successive instruction. “People have moved to Bainbridge from all over the world,” she continued. “We are going to the cemetery to explore their origins. We are leaving the IslandWood campus…”

Respectful etiquette can be taught. There are rules to follow. But respect that springs from empathy requires no enforcement. Respect and empathy, the makings of a steward.

![[Image description: A coyote walks in the forest at IslandWood's Bainbridge Island Campus.]](https://islandwood.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Copy-of-ABC-Conference-Speaker-Graphics-3.png)