IslandWood graduate students were featured in this recent Seattle Times article about House Bill 2078

Welcome back!

Hi, fam. Happy New Year! I am writing this from my cabin on a surprisingly bright yet cold day in January. If you’re like me (always doing something) you probably need a reminder to take a sip of water and then take a deep breath, so I invite you to do so now if you’d like to. I want to begin by sharing that this post is a reflection on the IslandWood Orientation and the 1st quarter of classes that ended in December of last year. It has been an interesting transition from New York City to Washington, as well as from orientation to teaching and taking classes.

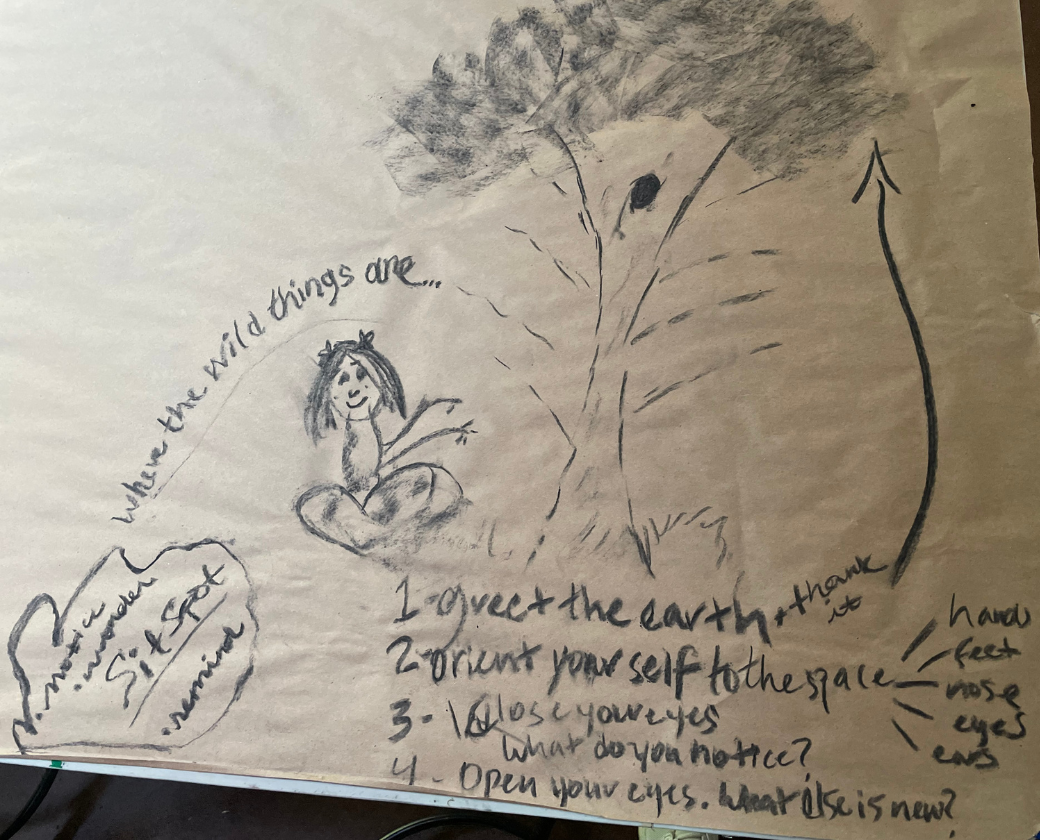

My ‘How to experience a Sit Spot’ instructions I made to share with children I’m teaching in the School Overnight Program.

As I reflect on the past 5 months, I am grateful that the IslandWood Orientation in the summer was such a beautiful time of slow transition into graduate school. We had some time to become familiar with this place and the spaces here on campus and on Bainbridge. I sunbathed on the grad and main campus, making time to read, sit, rest and walk outside often. One of my first friends in the cohort has an ideal cabin location so I would grab a blanket and book and/or speaker and walk from my cabin 2 min away to hers, to sit in one of the best sun spots on grad campus, in addition to her great company! Orientation programming included a great deal of time connecting with this sacred land of the Suquamish peoples, where Japanese, Filipino and Indigenous women from 36 Native tribes in Canada also called home. We were also guided in many activities that we would later do with students while teaching the Student Overnight Program (SOP) like solo walks, observing and drawing nature, becoming familiar with our tree neighbors, tasting and learning about delicious herbs, flowers and more at the garden, many of which can be found on the IslandWood Learn site found here.

Orientation to this place

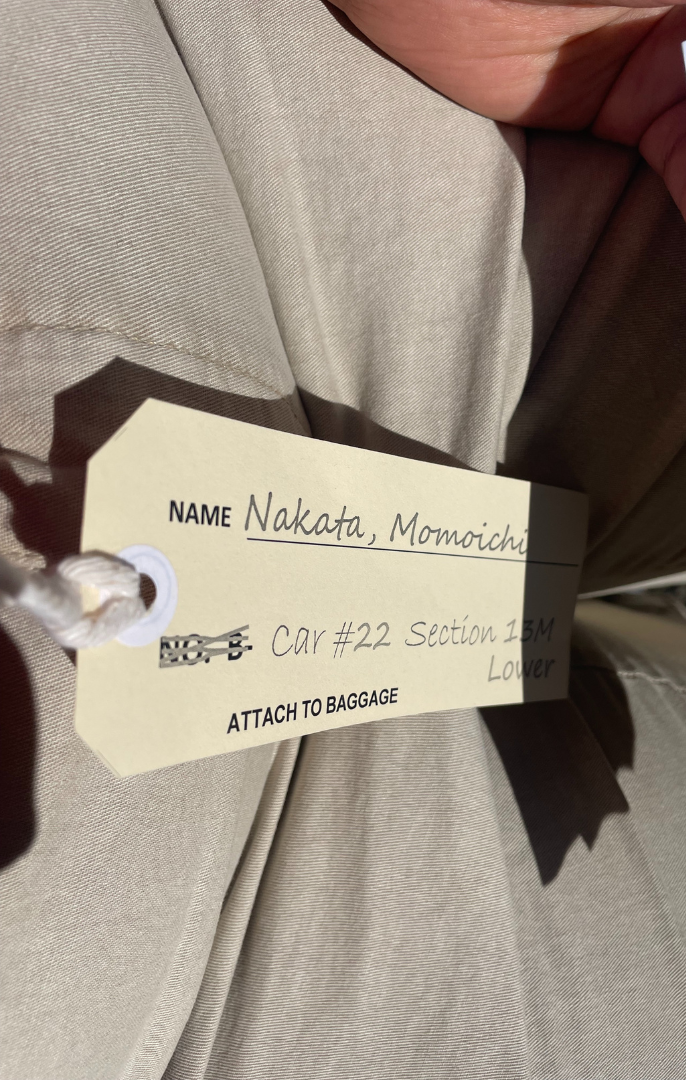

From viewing the baskets collected by Coast Salish tribal elder and educator, Vi Hilbert, here at IslandWood to visiting the Suquamish Museum, the Japanese Exclusion Memorial and later visiting the Bainbridge Historical Museum on my own, orienting to this place involved me learning all about the communities that exist here on the historical lands of the Suquamish. And similar to my community back in The Bronx in New York City, many groups of immigrants here have made this place home, creating rich communities that remain today. I’ve learned about the community halls set up by Filipino American communities, the Indipino families created after the Japanese Americans were forced to go to internment camps (with Bainbridge being the first place where Japanese Americans were forced to evacuate) and the rich history of berry fields that covered the island, that were tended and harvested by Americans of Japanese and Filipino descent, and Coast Salish peoples.

Sculptures by Artist Gloria Nusse showing where seven symbolic design elements illustrate an integrated cultural view of the Suquamish Tribe over time, as part of the “Ancient Shores – Changing Tides” exhibit at the Suquamish Museum, https://suquamish.nsn.us/suquamish-museum/

Thanks to the IslandWood Graduate Program staff prioritizing the connection to place during the month-long orientation, I’ve had a lot of personal space to slowly catch up to all of the changes of my move before beginning classes. Upon visiting Blakely Cemetery, for example, I felt a lot of anguish and grief just standing on the land. I felt disoriented, learned that Indigenous peoples were excluded from Blakely Cemetery and instead, many Indigenous folks were buried right outside the cemetery. I was unable to do more than just kneel and sob there for the remainder of our time- the weight of that truth was too heavy to hold.

Understanding the history of place

If you belong to a diasporic and transnational identity like me you might understand how important land is to culture, identity and belonging. I know there are others who also understand, like Original Peoples of this land in the U.S. as well as those who were forcibly brought here through slavery. Land is wealth as it is a means to both feed and provide income for the well-being of a family. Communities exist on land and so removal of peoples from land, limiting their access to it or making land inhabitable for people to live on is one of the biggest ways to extract wealth or the ability to create wealth from people. And because communities exist on the land it also disrupts access to their culture. My family’s histories span at least three known continents and though there are stories, traditions and even photos that provide clues to the past and which have influenced our present, there have been enough interruptions in our trajectories that I often wonder where would we be/how would we feel/what would we know/what would we be doing if there weren’t those interruptions from white settler colonialism and Imperialism. I could focus on the struggles here in the United Snakes for my immigrant families but I think going further back is useful. What if we never had to move to another part of the country to work in order to survive? What if we never had to work in sugar factories or make dangerous trips across countries to smuggle and sell goods? What if we never had to spend all of our time working or travel to other countries for work and send our kids to orphanages or distant friends’ houses to be taken care of? Would it have changed how we feel about ourselves? Would it have affected how we relate to family and community? Or to money, possessions, or purpose?

Photo of Nova in elementary school.

The connection between place and belonging

From what I’ve read and learned from friends who have attended graduate school, so much about academia can create isolationist behavior and feelings of inferiority, especially when you are a member of the global majority. Some issues are common and might be what you would expect, from managing time well to finish long readings, staying present during 3-hour long classes during the day and evening, to feelings of imposter syndrome during class discussions and on projects. Others are more unique to myself and others who are a part of the global majority, who also have experienced trauma and/or are neurodivergent. A lot about my upbringing, family and personal schooling history has come up a lot in the readings, videos and lesson planning in our day to day.

It also doesn’t help being so far away from home and from the community that has held me as I became an adult. Being distant from Caribbeans peoples especially Dominicans, from Bronxites, my blood and chosen family, and organizing community has impacted me greatly, making it challenging to be present or to connect with my peers at times. I miss processing, joking and debating issues with them, everywhere from the block, the park and building lobbies. As I mentioned in my first post, this place- New York City and especially The Bronx- are such a huge part of my culture and how I experience the world. Walk The Grand Concourse, E149th St. and 3rd ave, or even Broadway from Inwood down to Harlem or vice versa during the summer and you will see a little of what I feel. I realize more now that I am incredibly lucky to call New York home.

How identity and history of place show up in the classroom

Photo of identification tag of Momoichi Nakata, Bainbridge Island resident, taken at the Japanese American Exclusion Memorial.

If this is not part of you or your family’s history, you may wonder what this has to do with graduate school, education, or even being a teacher in general! Well, if you are someone who cares about people, the Earth, and creating a present and future with equity (especially if you are white educator) expanding your worldview to include multiple truths is important to unlearning the ways of being that contribute to this inequity in daily life and across systems.

I will share a story to help illustrate the importance of this understanding. In the 5th grade I was one of a handful of non-white students in my grade and there weren’t much more than that as a whole at my elementary school in Brevard County in Florida. We had a young substitute teacher for a few days while we covered what is expressed as “westward expansion” in our textbook, which many of us now know is actually white settler colonialism and Imperialism. One of the white boys in my class spent the entire class making jokes about my long, dark hair, tanned skin and small, almond eyes. He would end each remark with “that’s why my people killed your people. Your people are weak.” And he would accompany his so-called jokes and remarks, squinting his eyes, using his hands to narrow his eyes (an anti-Asian racist gesture that continues today especially since the start of the pandemic and anti-Asian hate crimes); and even mocking a racist war cry where he used one hand to cover and lift up one hand over his mouth as he chanted (a racist act that was even done on at political rally by a Trump supporter in 2018). This white boy was relentless and did this during the entire class, until I ran out of the room towards the end, sobbing, and escaped to the bathroom. I may not have known the history of racism and settler colonialism then but I had had enough experiences up until that point that expressed to me that I looked very different from the kids in class and that my physical features were not considered desirable, even before I entered school. I had experienced stares and racist comments about my appearance as early as a toddler from many people, strangers and family alike (see: colorism).

You can imagine it was challenging to concentrate in class during and even after that. No one checked in on me, spoke to the other student, addressed the class, or spoke to my parents or the other child’s parents about this incident. The burden was on me to decide how to navigate this racialization of my peers and the feelings that accompanied it. It did not matter to him that my family was not from the heritage of the Original Peoples here, or that my racial and ethnic identities were complex, with as much pain as there was joy because my family was multi-racial, with Taino and Dominican, Guarani and Paraguayn blood with clearly some European and African ancestry.

Unfortunately, I have many more horror stories in educational settings, informal and formal; and many people have (had) it so much worse especially, if your skin is more melanated than mine, your hair is coarse, including other identities like presenting as a girl or woman, being LGBTQ, belonging to a non-Christian religion, being Disabled, and/or being Neurodivergent. Whether it is visible or public or not, this behavior continues to this day in schools all across the U.S. So, it is important for educators to learn at least some of this history whether it is a part of their own identities or not.

Lessons From Plants

There’s a quote from Beronda L. Montgomery’s book, “Lessons from Plants” that helps contextualize this; it reads, “Notably the knowledge of plants—lessons from these organisms on being—shows us that you thrive or languish based on your ability to know who you are, where you are, and what you are supposed to be doing.” When we look at accessibility and opportunities of children and youth and how Montgomery goes on to explain this impact on development, from what can be perceived as a comparison of the development of children and youth to the growth of a bean seedling from an experiment she did in kindergarten. She writes,

Beronda Montgomery’s book, Lessons from Plants

“The plants, I was surprised to see, were not all the same: Some were short and stocky, while others were tall and spindly. The teacher explained that these differences depended on how much light we’d each had coming through our window. If the windowsill was shady, the plant would grow tall to try to reach the light. This was my first exposure to an essential feature of plants — that they are exquisitely attuned not just to light levels, but to a whole array of environmental conditions.

Plants are aware of light, water availability and moisture level, and nutrient abundance in the soil. They perceive changes in these factors as they scan the environment and assess what responses they need to make. Based on the information they gather, they are able to alter their behavior, morphology, and physiology in response to changes in their surroundings.”

This is one of my absolute favorite passages from her book and in general, from the study of environmental science, education and justice work. This passage exposes a lot of what my first quarter of classes affirmed and taught me, with the first lesson being that we can learn so much from observing nature outside of humans on a psychosocial level and also about how we learn and two, that place, environment and all of the conditions of one’s environment greatly impact how we develop as individuals and the roles we take in our communities and in larger society. In the story above, Montgomery explains that the beanstalks are not only aware of what is happening around them, they are also responding in ways with these changes in their environment in mind.

Photo of two of the backs of Nova’s friends in front of sculpture at Departure deck Eagle Harbor, at the Japanese American Exclusion Memorial. The rusted steel sculpture is by Vaughan, Washington artists Anna Brones and Luc Revel. https://bijaema.org

As educators and organizers, it can often be challenging to work with people all day long, young, adults and elderly alike. We wonder why this person acted or responded this way or that. We wonder why this person doesn’t think like we do. We wonder why we might change how we act around certain people or why others change how they act around us. I think that students in informal and formal educational settings are constantly assessing the conditions of their environments and responding to them differently. One student might be familiar with your tone and approach and might behave like they always do while another student might change if this is all new and they want to be noticed or even impress you. One truth that I’ve sat with throughout the past few months has been that we as educators hold so much power in traditional educational settings, and if we desire equity in our classrooms, we must not only give up power, but also be ready to collaborate as co-conspirators with our students. This means doing a lot more listening and observing.

Anyone can learn so what are you paying attention to?

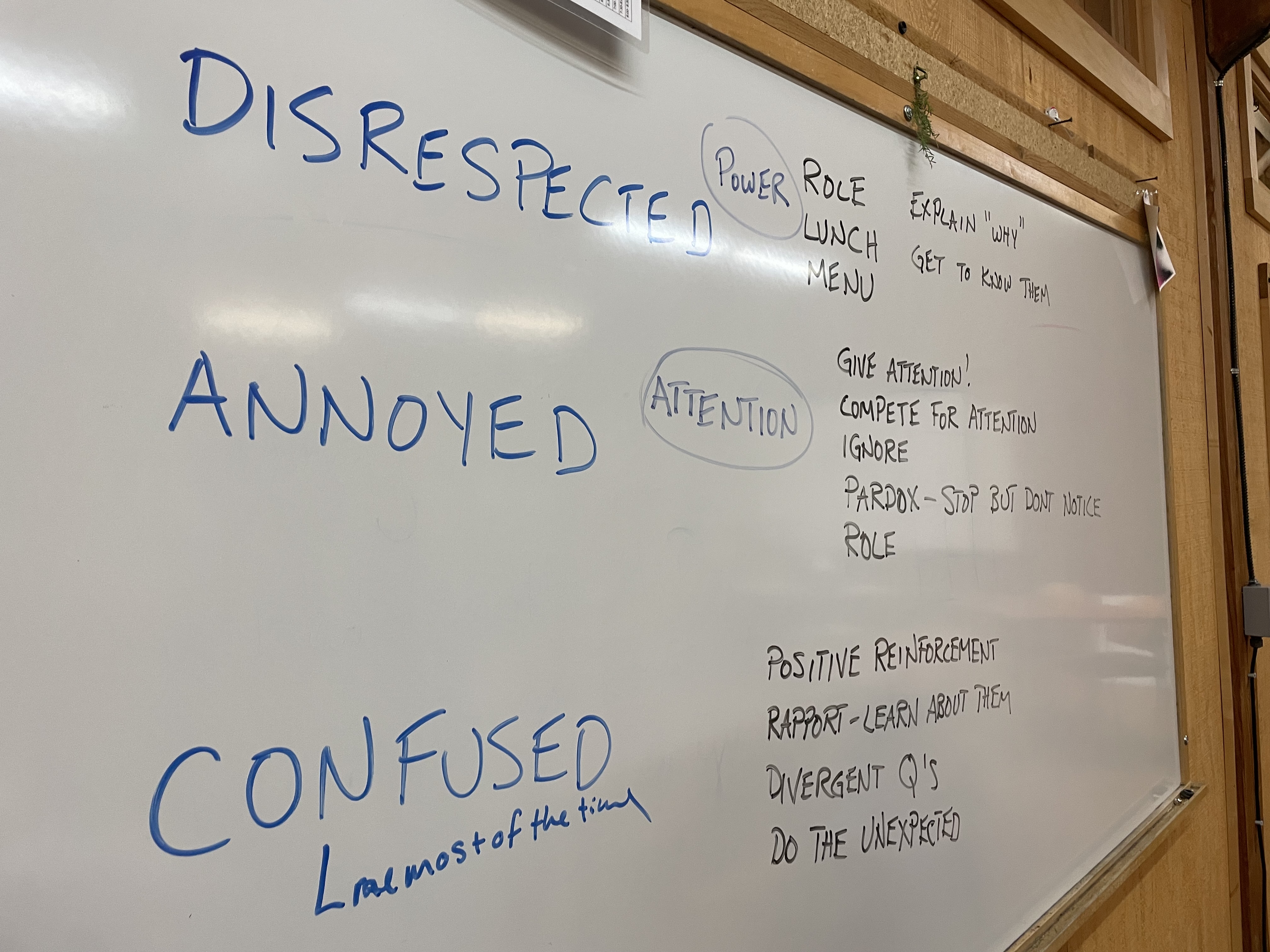

A practice we have been doing regularly in our preparation before teaching at the Student Overnight Program (SOP) has been analyzing behavior from students that have historically been labeled as ‘disrespectful’, confusing or annoying. What we have been taught to perceive as disrespectful like talking while we are talking is usually an example of students wanting more power in how they learn and what they do. What we may perceive as confusing likely is the student requesting positive reinforcement and a desire to connect to you. What we may perceive as annoying, is likely the student seeking attention because they feel ignored or not important. When we reflect on our impact on students and their learning journeys, we cannot change the histories that come with them, and we shouldn’t try to change them either to fit with the boxes and spaces that have historically dehumanized us all. However, we can pay close attention to their needs that you can meet in an educational setting- needs like attention that encourage a healthy self-esteem, connection via positive and safe teacher-student relationship that helps them identify teachers as part of their support system and community, and power so they can practice critical thinking, understand their learning ecosystem and become active participants in the building of their future where they are comfortable making decisions, communicating needs and caring for others.

EEC Classroom whiteboard

At the core of equity initiatives is the need to see the whole person and not the broken pieces we are taught to see and “save”, ignore or exclude because it is easier than putting the work to see their full delightful, mischievous and curious selves expressing their needs and interests through their actions and words or lack thereof. The places and environment they come from and currently reside, and the spaces we curate, what opportunities we collaborate with them to create, or what work we do not take on, has everything to do with their histories, their full humanity, and how we view our relationship as educators to the worldwide movement for liberation. If we believe as bell hooks has taught us, that “To educate is the practice of freedom,” {it}”is a way of teaching anyone can learn.

And this is true not just for students and people who are of the global majority or who have identities that have been historically oppressed; it is also true for those whose histories are more closely tied to the oppressors because their humanity and liberation is also at stake if we do not teach to practice freedom and if we do not teach with the understanding that everyone is capable of learning. It is a commitment to the belief that no body is disposable, which is a concept that African/Black organizers who are Womxn, Femmes,Trans, Disabled and Survivors of Violence have taught us through their creation of Transformative Justice. This is something I can share more about in the future and how it connects to informal learning environments. For now, I will leave you with the following, “Have you thought about how the place and environment you come from have influenced you?” How has it shaped you? Were you shielded from experiencing things others weren’t shielded from? What is the history of the land where you reside? Of the animals, lands, waters and plants? Of the schools and communities? Of the people? How has knowing or not knowing this history impacted you? How does this show up in how you learn outside of school, or how you relate to community?

Hasta la próxima/Until next time,

In solidarity,

nova

P.S. Within the post, Nova referenced Beronda Montgomery’s book, Lessons from Plants, which is part of the graduate reading list. If you’re interested in other readings our faculty share with incoming graduate students to help build the foundation for their time at IslandWood, please check out more info here.

P.P.S. If you haven’t already, subscribe to our newsletter to stay in the know about blog posts, news, and events!